Confidence is high. I repeat, confidence is high.

Date: 1954-06-13

Amidst news that the Soviets may be developing an Intercontinental Ballistic Missile (ICBM), their so-called "R7" project, we have been tasked with producing a rocket capable of reaching from Western Europe to Moscow.

The objective is simple in its audacity: Increase our rocket's capabilities from 600km downrange to over 3,000km, creating an Intermediate-Range Ballistic Missile (IRBM) before the two superpowers.

We have a range of new technological innovations on our side:

- We have developed a newer, lighter, aluminium alloy for our rockets.

- We have improved our existing main rocket engines (on par with the Russian RD-102).

- We have improved our avionics to the point we can control our rocket launches.

- We have also developed a new upper stage rocket engine similar to the US AJ10-27 engines, which use nitric acid/aniline and are the latest generation of the SR-1 engines we flew right back in 1951.

Combining these we also need to take account of a new limitation: Our current launch pad can only support a 20 tonne rocket. To maximise our capabilities we will need to use every bit of that 20 tonnes, while minimising the weight of our payload.

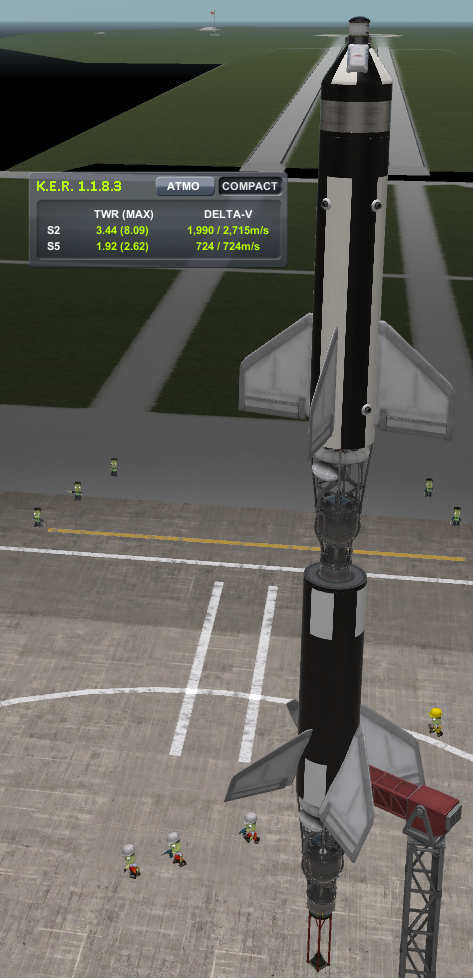

Presenting the SR-2d, coming in at 19,906kg:

The SR-2d has a guided lower stage which carries an unguided upper stage that has 3 of our new engines:

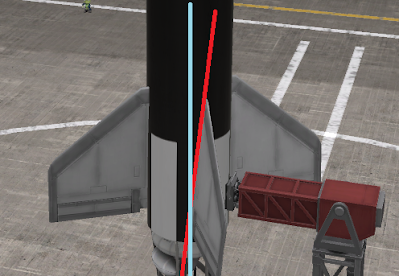

The upper stage is deployed using small, quick-fire, solid fuel kick-boosters which not only solves the ullage problem for the engines but also spin stabilises the stage:

The most fragile bit of the rocket is the new upper stage engines. These engines are, as of yet, untested. If any of the engines fails, the rocket will very likely fail to meet its objective. They are, however, required, since the engines are only rated for 52 seconds and there is more than 52 seconds of fuel to go through (3x as much, to be exact!). The extra thrust also minimises the opportunity for gravity to take hold, improving overall efficiency.

Current testing is, however, showing positive results. I estimate a roughly 70% chance of success. For our test flight we'll be yeeting it across the Nile Delta in Egypt, over 3,000km to the east, where it will burn up on re-entry in to the atmosphere.

Next Post: Onwards and sidewards

Comments

Post a Comment